Silicon Valley Controls the Internet

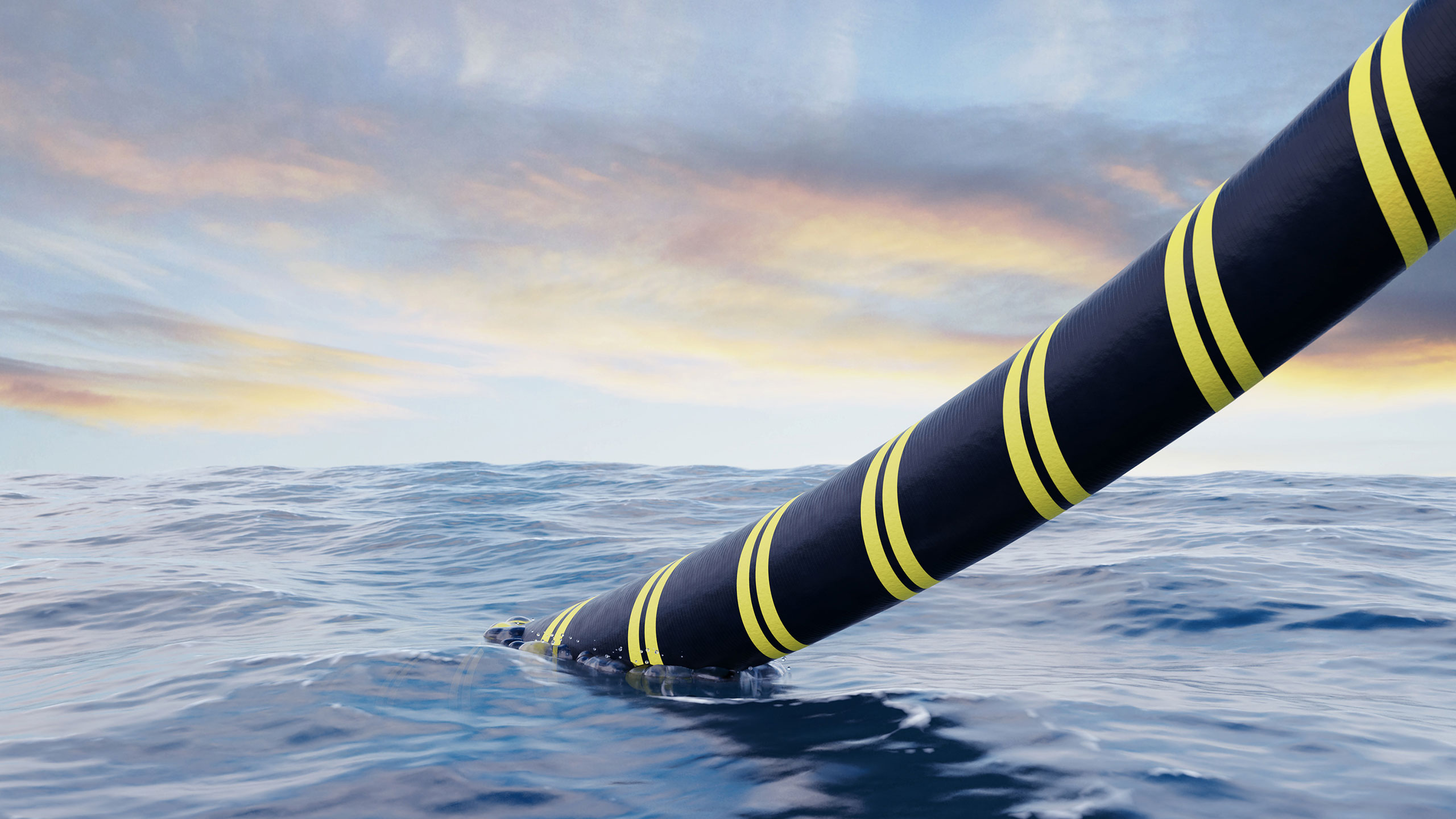

Increasingly, it is true in at least one respect, the internet can seem immaterial. A post-physical environment where things like viral posts, virtual goods, and bitcoin transactions just happen. But creating this illusion requires a truly gigantic and rapidly growing network of physical connections. It turns all those ones and zeros into our internet experience where these fiber-optic cables connect countries across oceans. They consist almost entirely of cables running underwater, approximately 800,000 miles of stranded glass that make up the physical international internet.

And until recently, the vast majority of installed submarine fiber optic cables were controlled and used by telecom companies and governments. Today that is no longer the case, in less than a decade, four tech giants Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon have become by far the largest users of undersea capacity. Before 2012, the share of global submarine fiber capacity used by these companies was less than 10%. Today it is about 66%. And these four are just getting started, say, analysts, submarine cable engineers, and the companies themselves.

In the next three years, silicon valley is on track to become the main financiers’ of undersea fiber.

By 2024, the four are expected to have a joint stake in more than 30 long-distance undersea cables, each up to thousands of miles long, connecting every continent in the world except Antarctica. In 2010, these companies were involved in just one of those cables: Google’s Unity cable, which connects Japan and the United States. Traditional telcos have reacted with distrust and even hostility to growing tech companies. and predatory demand for global bandwidth. Industry analysts have raised concerns about whether we want the world’s most powerful ISPs and marketplaces to own the infrastructure on which they are deployed.

These tech giants’ involvement in the cable-laying industry also lowered the cost of data transmission across the oceans for everyone, including their competitors, and helped the world increase international data transmission capacity by 41% in 2020. Undersea cables can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, Installing and maintaining them requires a small fleet of vessels, ranging from survey vessels to specialized cable-laying vessels employing all sorts of robust underwater technologies to bury cables beneath the seabed.

Sometimes they have to run the relatively fragile cable, in places as thin as a garden hose, to depths of up to 4 miles. All of this must be done while maintaining the correct cable tension and avoiding hazards as diverse as seamounts, oil and gas pipelines, high-voltage power lines for offshore wind farms, and even shipwrecks, says Howard Kidorf, partner manager at Pioneer Consulting, which advises companies on design and construction supported by subsea fiber optic cable systems. In the past, laying overseas cables often required the resources of governments and their national telecommunications companies. Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon made more than $90 billion in investments in 2020 with hopes to increase bandwidth in more developed parts of the world and upgrade neglected segments of aging network assets.

Here is where things get

Not the whole story

Imagine if Amazon owned the streets and highways...

Their entry into the undersea fiber laying business was inspired by the growing cost of buying capacity on cables owned by others. But is now driven by an insatiable demand for ever more terabytes of bandwidth. By building their cables, the tech giants are saving themselves money over time that they would have to pay other cable operators. That means the tech companies don’t need to operate their cables at a profit for the investment to make financial sense.

Indeed, most of these Big Tech-funded cables are collaborations among rivals. The Marea cable, for example, which stretches approximately 4,100 miles between Virginia Beach in the U.S. and Bilbao, Spain, was completed in 2017 and is partly owned by Microsoft, Meta and Telxius, a subsidiary of Telefónica, the Spanish telecom. In 2019, Telxius announced that Amazon had signed an agreement with the company to use one of the eight pairs of fiber optic strands in that cable. In theory, that represents one-eighth of its 200 terabits-per-second capacity enough to stream millions of HD movies simultaneously.

Sharing bandwidth among competitors helps ensure that each company has capacity on more cables, a redundancy that is essential for keeping the world’s internet humming when a cable is severed or damaged. That happens around 200 times a year, according to the International Cable Protection Committee, a nonprofit group.

Sharing cables with ostensible competitors as Microsoft does with its Marea cable is key to making sure its cloud services are available almost all of the time, something Microsoft and other cloud providers explicitly promise in their agreements with customers, says Frank Rey, senior director of Azure network infrastructure at Microsoft. Tech companies have spent decades arguing in the press and in court that they are not “common carriers” like telcos if they were, it would expose them to thousands of pages of regulations particular to that status. There is an exception to big tech companies collaborating with rivals on the underwater infrastructure of the internet. Google, alone among big tech companies, is already the sole owner of three different undersea cables, and that total is projected by TeleGeography to reach six by 2023.

Google has repeatedly declined to disclose whether or not it has or will share capacity on any of those cables with any other company.

Google has built and is building these solely owned-and-operated cables for two reasons, The first is that the company needs them in order to make its own services, such as Google search and YouTube streaming, fast and responsive. The second is to gain an edge in the battle for customers for its cloud services. All of these ownership changes to the infrastructure of the internet are a reflection of what we already know about the dominance of internet platforms by big tech.

The ability of these companies to vertically integrate all the way down to the level of the physical infrastructure of the internet itself reduces their cost for delivering everything from Google Search and Facebook’s social networking services to Amazon and Microsoft’s cloud services. It also widens the moat between themselves and any potential competitors.